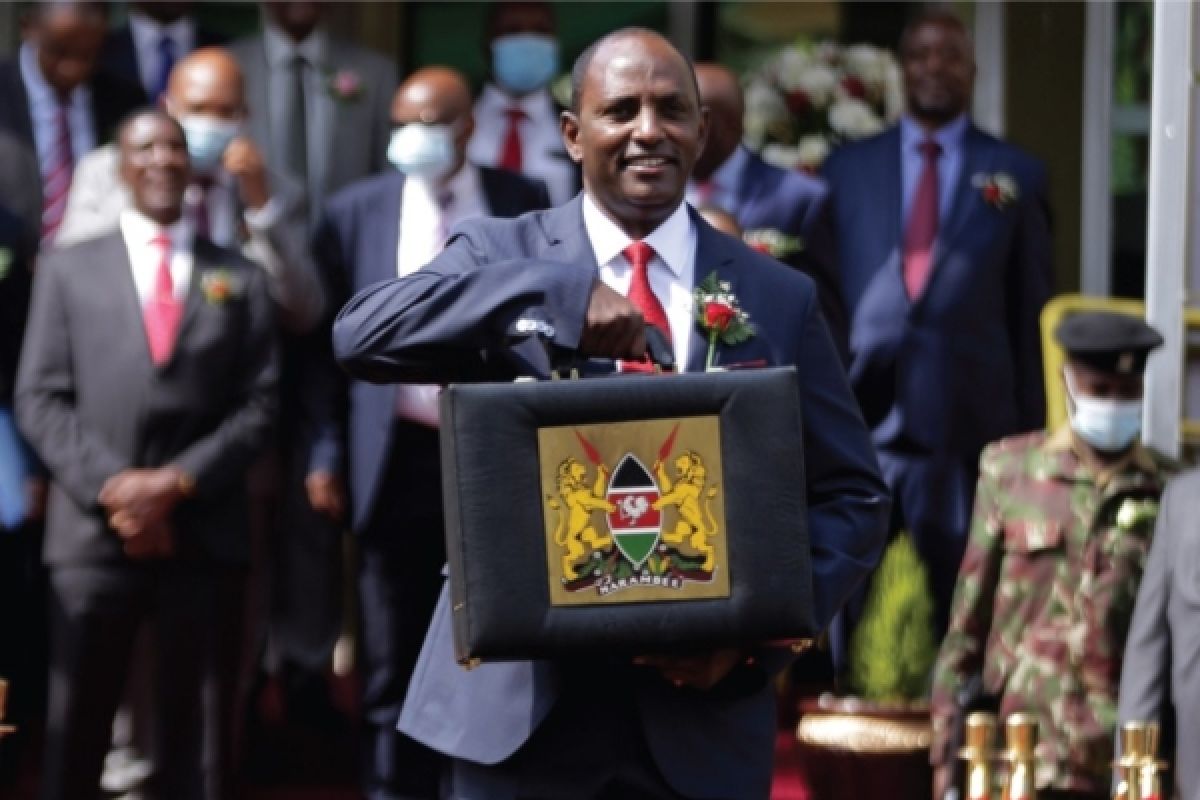

Kenya grapples with debt crisis

As Kenya’s lockdown bills skyrocket, the country is faced with a new era of austerity, government borrowing and tax hikes. By Zachary Ochieng in Nairobi.

Over 160,000 Kenyans signed an online petition in April to stop the International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailing out the East African powerhouse.

Uhuru Kenyatta’s government had requested a $2.5 billion loan from the IMF to help pay for the country’s series of harsh Covid-19 lockdowns, estimated to have cost the National Treasury $8.95 billion between March and November 2020 alone.

Jefferson Murrey, who set up the Change.org petition, said previous loans to the Kenya government ‘have not been prudently utilised and have often resulted in mega corruption scandals’.

‘The scandals have not deterred the ruling regime from appetite for more loans, especially from China.

Right now, Kenyans are choking under the heavy burden of taxation, with the cost of basic commodities such as fuel skyrocketing, and nothing to show for the previous loans.’

It’s a view shared by many in Kenya, which has seen mass job losses and hunger as a result of the country’s lockdown measures.

Mwihaki Mwangi, a social media activist, called on the IMF to ‘stop lending money to the Kenyan government’, adding: ‘It ends up in few corrupt pockets. No change in living standards to the common citizens. We are becoming poorer and poorer. Heavy taxes levied on our meagre salaries. Reverse the loans. We don’t need it.’

But in a statement, the IMF defended Kenya’s continued borrowing. Its deputy managing director, Antoinette Sayeh, said: ‘The Kenyan authorities have demonstrated a strong commitment to fiscal reforms during this unprecedented global shock, and Kenya’s medium-term prospects remain positive.’

Despite its public show of support, the IMF made it clear that Kenya will have to introduce austerity measures in return for the bailout, warning the country faced even ‘sharper fiscal consolidation or much more expensive borrowing on commercial terms’ without its help.

Kenya’s public debt is expected to peak at 73 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022-23.

As part of the loan agreement, the Kenyan government will be expected to discipline itself and raise more taxes, cut expenditure and narrow the deficit – moves unlikely to go down well with Kenyan voters.

In recent months, the government has already raised taxes on fuel, putting a strain on households’ pockets. In addition, public servants will now contribute to their pensions and loss-making government businesses will be privatised, merged or closed, which will impact jobs as well as the economy.

Musalia Mudavadi, leader of the opposition party Amani National Congress and Kenya’s one-time finance minister and vice president, said the regime that takes over from the ruling Jubilee administration after the 2022 General Election will face a herculean task in resuscitating an economy ravaged by huge public debts.

‘We are doomed as a country,’ said the presidential election contender. ‘It is the common man who will pay these debts. The cost of everything goes up and there will be more thieves as a result of unemployment.’

He added: ‘No government should force a nation to incur a debt for the purpose of funding corruption, theft, wastage or white elephants that have no economic or financial value. The economy is bleeding and unless the national treasury restructures and reschedules the national debt, the situation will worsen.’

Dr David Ndii, an economist and a harsh critic of the Kenyatta administration, concurred.

According to him, the IMF programme is a structural-adjustment loan, which will come with some pain.

‘It comes with austerity – tax raises, spending cuts, downsizing – to keep Kenya credit-worthy so that we continue borrowing and servicing debt. ‘IMF is not here for fun.’

The treasury cabinet secretary, Ukur Yatani, has argued that the amount is necessary to fight the Covid-19 pandemic and reduce debt vulnerabilities. According to him, access to vaccines is critical, and help from the international community is urgently required.

He has blamed the excessive borrowing by the Kenyatta administration on shrinking tax revenues in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Like the UK and South Africa, Kenya has been beset by corruption claims concerning its Covid-19 procurement processes.

Last year, a report by Auditor General Nancy Gathungu revealed how $71 million was lost in a scandal involving medical supplies at the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA).

The Auditor General’s report also revealed so-called fly-by-night companies that were awarded tenders only a few months after registration and could not be deemed to have the necessary experience and capital to supply specialised medical equipment and products.

It did not help matters that President Kenyatta has admitted that his government loses $18.6 million to corruption every day, without mentioning what steps had been taken to recover the funds and prosecute those behind the theft.

Even after the anti-graft watchdog recommended the prosecution of those found culpable, no one has been convicted of corruption almost a year later.

Corruption aside, Kenyatta’s eight-year rule has been decried by opponents for its reliance on borrowing.

The size of the budget has been increasing while tax collected by the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) has stagnated, resulting in a deficit that has forced the country to go on a borrowing spree.

The Parliamentary Budget Office, which advises legislators on financial and budgetary matters, has already warned against unrealistic budgets.

‘The actual fiscal deficit including grants averaged 7.6 per cent in the period FY 2013/14 to FY 2019/20, compared to an average target of 4.0 per cent during the same period, representing a 3.6 per cent deviation,’ the office warned.

Even more worrying is the fact that debt accumulation, including from international capital markets (Eurobond), has seen Kenya commit more than half of taxes to loan repayments.

Despite falling tax revenues, the Kenyatta government plans to add over $9.1 billion to its public debt mountain in the 21/22 financial year, according to the 2020 Budget Review and Outlook Paper, as the government looks to fund infrastructure project such as new roads, a modern railway, bridges and electricity plants.

The country’s ballooning public debt is projected to reach 69.8 per cent of GDP by 2023, an increase of over 10 per cent on pre-lockdown levels.

Meanwhile, the amount the government has to repay in interest is expected to increase from 9.8 to 12.9 per cent of GDP between 2019 and 2023, severely reducing funds that are meant to improve service delivery to citizens.

In a desperate attempt to defend the high debt appetite, treasury mandarins have compared Kenya with other countries around the world whose public debt exceed their economic output, such as Japan, estimated to have a public debt to GDP ratio of 240 per cent.

After months of dilly-dallying, Kenya finally joined the G20 Debt Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in order to defer some of its external debts payments, amounting to $630 million. A further $545 million due within the first half of 2021 have been rescheduled.

Kenya’s appetite for debt, though, remains insatiable. The treasury has requested parliament increase the debt ceiling of nine trillion Kenya shillings (about $82 billion). It is also said to be considering tapping into the international capital markets with its fourth Eurobond issue in less than seven years to help offset part of its debt obligations in the next three months.

But with the country expected to cross the milestone one trillion shilling ($9.17 billion) in debt repayments by the end of 2021-22, and the country’s credit rating being recently downgraded by S&P, Fitch and Moody’s Investor Service alike, the days of reckless borrowing may be coming home to roost for Kenyatta sooner than he thought.